The Contenders

General William Henry Harrison (Whig-OH) – No anti-Jacksonian was more like Jackson than Harrison. His leadership led to a great victory (the Battle of Tippicanoe, earning him the nickname “Old Tippicanoe”) in the War of 1812. He was a towering figure, a hard drinker, and the most charismatic man in American politics since, well, Jackson. As a Whig, though, he believed the Congress needed to take back more power to save the people from the Panic they created. He was most outspoken about wanting to establish a one-term limit on the presidency, spitting in the face of Jackson's benevolent dictatorship.

The Fight

Before 1840, elections were usually about one of two things: policy or geography. State electors voted for the guy who believed what they believed, or lived the closest. That wouldn’t fly this time. The stuffy, wealthy priss was a Populist who held influence from New York to the South, and the drunken brawler was a pro-big business guy who enjoyed support from the West to New England. For the first time, this election would be decided entirely by personality, a popularity contest.

The sort of wild character attacks we see in elections nowadays really started right here in 1840. The Democrats took the first swing. A Baltimore Democratic newspaper wrote that the extremely fucking old Harrison should just collect his military pension and sit at home in his log cabin drinking hard cider. The Whigs turned that right around and called Harrison the “Log Cabin” candidate, a regular guy who was in touch with the people.

Both parties turned the election process into an all out media blitz, with speeches and songs and rallies and banners and buttons. The Whigs held events in log cabins, passing out hard cider to all who attended. Their slogan “Tippicanoe and Tyler Too” (referring to Harrison’s running mate John Tyler) had a much better ring to it than Van Buren’s nickname, “Old Kinderhook.”

Whigs voraciously went after Van Buren’s prissy Kinderhook image. He had a long, public record of unbridled ambition, the sly fox pulling Jackson’s strings, controlling the people’s destinies behind their backs. The Democrats turned that image on its head, opening up O.K. Clubs, which brought the common man into the big world of politics.

Van Buren’s mighty political machine was facing its first major foe, and imminent defeat. Up until this point, only Adamses lost re-election. Could a political genius like Martin Van Buren really be as unpopular as an Adams?

The Title

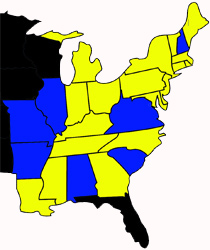

Harrison kicked Van Buren’s ass, hard core, 234-60 electoral votes, even winning Van Buren’s home state. The Harrison administration is nothing to speak of because he died within a month. His Ascendancy, President Tyler alienated his entire party by blocking their attempts to resurrect the Bank of the U. S., and went totally off the reservation by supporting the annexation of Texas. Annexation became the platform that got Democrat James K. Polk elected in 1844.

Harrison kicked Van Buren’s ass, hard core, 234-60 electoral votes, even winning Van Buren’s home state. The Harrison administration is nothing to speak of because he died within a month. His Ascendancy, President Tyler alienated his entire party by blocking their attempts to resurrect the Bank of the U. S., and went totally off the reservation by supporting the annexation of Texas. Annexation became the platform that got Democrat James K. Polk elected in 1844. The ripples of this election influenced every election to come. The image of the Log Cabin became the symbol of westward expansion, and presidential candidates who invoked the Log Cabin usually got a huge bump (more on them in later installments). The term “O.K.” survives to this day to describe something pretty good but not great, much like Van Buren. Most importantly, the gloves came off. Everything about a presidential candidate’s persona and personal history became relevant to the election.

As for Van Buren, that’s a story for another time.

Next Up – Election 1848: Holy Shit! Slavery!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Friends, please sign your comments, so I know it's you. I will most likely delete Anonymous comments.